Jonathan Stokes

The Michael Brown Jr. memorial in Ferguson.

It has been 10 years since Michael Brown Jr. was discriminated against and needlessly killed by former Ferguson Police Department officer Darren Wilson. To reflect on the culture-shifting tragedy that happened less than five miles away from the UMSL campus, the university hosted Ferguson Remembered on March 11. The event was a collaboration of UMSL’s honors college, school of social work, college of nursing and department of music.

Honors college professor Rob Wilson stated, “The 10-year anniversary was coming, and I realized these students were only eight to nine years old. They don’t even know what we’re talking about.”

This knowledge gap inspired the first part of the two-part event, a bus tour through Ferguson led by the executive director of Forward through Ferguson, Annissa McCaskill.

Students gathered at Provincial House at 4 p.m. to board the tour bus. The tour through Ferguson offered insight into Brown Jr.’s life, humanizing him while tracing the steps that marked the day of his passing and the events that followed.

Bus Tour

First Stop: Normandy High School

McCaskill immediately sets the scene for Michael’s life by visiting the high school he graduated from just days before his death.

Brown Jr. had just turned 18 in May and graduated from Normandy on August 1, 2014, after attending summer school. He was set to start school at Ranken Technical College on Monday, August 11. On Saturday, August 9, he was killed.

McCaskill goes on to say that at the time, only two-thirds of Normandy students graduated, with only 30% of those graduates going on to pursue degrees. This reminded her of a conversation she had when she first met Michael Brown Sr. and his wife, Call Brown.

McCaskill says, “They asked if we could meet and have lunch at a restaurant in Ferguson. No problem. Let’s have lunch. It was a great lunch. And then, before we left, Michael said, ‘This is the last place I saw my son alive.’ In the days between when he graduated and when he was killed, he had sat his son down, had lunch with him, said, ‘Okay, you’re going to college. You’re going to do this. You’re going to get this HVAC degree. You’re going to do all the things that I didn’t do.’ And then the next time he saw his son, he was dead.”

Second Stop: Buzz Westfall Plaza

The bus stops directly in front of the parking lot, where McCaskill recounts the flood of international press that made themselves at home following the tragedy. She states that the press, such as CNN, Fox and Al Jazeera, camped out in the lot along with others. They had chairs set up, “doing 24/7 interviews” with our citizens who were going about their day.

Pointing to the lot, McCaskill says, “This is where the fires were. This is where a lot of the rioting happened. People think of City Hall … but this is where the tear gas happened. This is where people were being hit with rubber bullets. This is where you had the police in the gear where you couldn’t see their faces, so you didn’t know who you were being engaged by. And if you lived in the area, just minding your business trying to go shopping, you had to go past all these strangers who basically had decided they were going to camp out in your community and treat you like a spectacle.”

Third Stop: Ferguson Supermarket/ Elite Market & Grill

McCaskill tells us this is where it all started. Michael and his friend enter the market to buy Swisher Sweets and then walk to his grandmother’s apartment. She adds, “You all can go online and read it for yourselves, but in the end, I’ll say this, whatever did or didn’t happen here, there’s no excuse for a young man being killed over it.”

There were other police [officers] in Ferguson working on a call regarding some sort of interaction here. We don’t even know if that was Michael Jr, just a description was given of two young Black males. We’re in Ferguson. The majority of the population in Ferguson is Black.”

McCaskill also recounts that Ferguson is a predominantly Black community, in which many migrated over from Kinloch due to the Airport expansion. In 2014, over 72% of Ferguson’s population was Black, yet the police department had only three Black officers out of 53. This stark reality, coupled with Ferguson’s history as a sundown town, highlights the ongoing systemic issues surrounding Brown’s tragic death.

Third Stop: Canfield Green/ Renewal Heights Apartments

Here, McCaskill asks our bus driver to park in the lot near the playground at the entrance to the neighborhood. She stops the group on the sidewalk, parallel to a large rectangle in the street that leads into the heart of the apartment complex. There are messages written within the rectangle next to his name. McCaskill tells us this is where Michael Brown died.

From the time Wilson approached Brown to the time he died, only 90 seconds had passed.

McCaskill adds, “Just after noon, Michael was killed, and he was signed into morgue custody at 4:37 p.m.” Brown’s body was left in the middle of the street for four hours and 30 minutes. To pay respects, the group shared a moment of silence for four minutes and 30 seconds.

As the group stands on the sidewalk facing his memorial, multiple cars pass in a constant flow of traffic, with residents coming and going. McCaskill then says, “Imagine all of the people out here, and seeing 26 police units coming in, and Michael’s body was just laying here. And they didn’t put him in the ambulance. And he was uncovered for a good amount of the time. The only cover he received was when a neighbor went and got a sheet and covered him. They didn’t even give him the dignity of covering his body.”

Fourth Stop: Formerly QuikTrip, Currently Urban League

The final stop was once a QuikTrip that, after catching fire, became an unforgettable image and landmark, marking the beginning of the unrest in the area. McCaskill shares that QuikTrip chose not to invest in the community after it burned down. However, QuikTrip’s parent company worked with the Urban League, and the Urban League was able to invest back into the community.

“Until they got here, there was nothing left here other than an empty reminder of what happened when the world caught on fire. So, a lot of redevelopments you see in this side of town are because Urban League decided to anchor, and invited other people to also come in to anchor and bring revitalization back,” said McCaskill.

She adds, “I want to press upon you that Michael’s death was a tragedy. It did not have to occur. It’s something that can still happen, and we know that it still happens. What most people don’t realize is that when Michael was killed, he and his family were homeless. Their house had burned down, and they were living in a hotel with six other children. But yet they stepped in front of a camera every day to demand justice for their child and for everybody’s child, so that this never happens again. And they are still fighting.”

McCaskill’s final statements were the preface to the in-depth and just as emotionally evoking second part of the event. The bus tour ended in time for the group to head to Touhill for the discussion panel with McCaskill as one of the speakers.

Panel Discussion

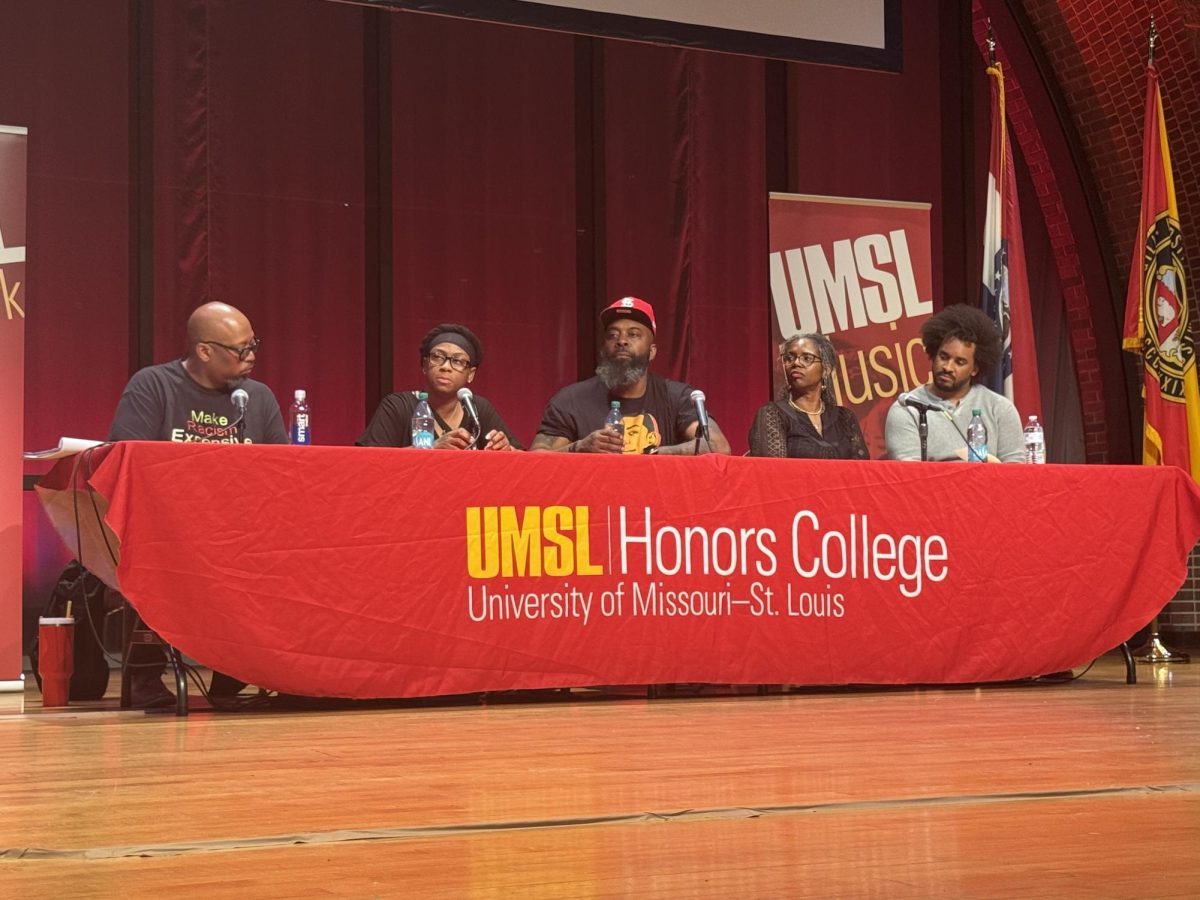

After opening remarks from honors college professor Rob Wilson, a performance from the Arianna String Quartet set the tone for the evening. The group performed “Elegy: A Cry from the Grave,” a piece composed by Carlos Simon to honor Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and Michael Brown. Then, Dr. Jason Vasser-Elong read his poem “I Saw Mike Brown at the Library,” which imagines a scenario in a world where his life wasn’t taken. Following the emotional performances, the panel discussion commenced.

Moderator and CEO of the Community Health Commission of Missouri, Riisa Rawlins, invited the panelists to the stage to introduce themselves, beginning with Michael Brown’s family members.

Michael Brown Sr., the biological father of Michael Brown Jr., began by telling the audience that when his son graduated from high school, eight days before his untimely death, Brown Jr. said that “the world was going to know his name.” Brown Sr. says it was this comment that motivated him to persevere and give voice to his son, ending his introduction by saying, “I am him. He is me. I am the voice.”

His wife, Call Brown, said her calling was to support her husband through “the biggest fight of his life,” which led her to co-found The Michael Brown Sr. Chosen for Change Organization. The non-profit focuses on grief support for families experiencing traumatic loss.

Dr. Duane Foster Martin, David Dwight IV and Annissa McCaskill rounded out the panel, each having unique perspectives and relationships to the Brown family and the movement that the killing inspired.

Martin, Brown Jr.’s former drama and music teacher, drove students to the first vigil, where they lit candles and mourned. During the vigil, students noticed a heavy police presence, despite there being no unrest in the area. Then, a student told Martin that he ought to get out of the area because it seemed like something was “about to go down.” The group then left and went to a pizza restaurant, where a television showed that the QuikTrip near the vigil was in flames, thus starting the chaos in the area.

After some conversation about what once was, the panel discussed what could be in the future. When asked how future generations will understand the truth and impact of the events in Ferguson.

“I think a huge way of doing that is storytelling and servicing people’s stories, keeping them present with us,” says Dwight, adding that there are many beautiful traditions including the history of oral storytelling and negro spirituals in the Black community.

He continues, “But I think in the future, social media and all of this division … is creating space for alternate truths … it’s a danger to the youth that are coming up and exposed to that.” Concluding with the suggestion that if we’re well-versed in the stories of our communities, we can use storytelling to pass knowledge forward.

During the question-and-answer portion of the evening, UMSL student and president of the Minority Student Nurses Association, Hasset Asfaw, mentions that she was only 12 years old when the unrest in Ferguson occurred.

“We saw it on social media, we heard it at school, and it’s crazy to say that we lived it, but it traumatized us. We’re scared to do certain things now,” said Asfaw. She then asked the panel a poignant and timely question, “How do we use our voice without fearing the consequences?”

Dr. Martin answers, “I always tell my teachers that the greatest teachers are those who don’t fear losing their jobs … who teach like they’re going to teach forever, and when you live with that fear, it will block you from your blessings, so to speak. So I would just say remove the fear of the consequence, especially when you have your like-minded tribe with you. Strength in numbers.”

Another audience member asks the panel about specific “wins” and successes in civil rights progress after such a tragedy, to which Call Brown answers with a sobering reflection of the ongoing struggles within the community.

“Well, it would be hard to talk about ‘wins’ when I continue to get phone calls at 3, 4 o’clock in the morning, and people still losing their children. Until I can stop getting those phone calls, we ain’t won,” said Brown.

Reflection

The event educated the younger generation, many of whom were not yet teenagers and were unaware of the weight of racially motivated injustices. Considering UMSL’s student demographic is predominantly white, thus not being directly affected by systemic racism, further distances a large portion of the student body from important discussions about race and racism. This event and the education it provides help to close these gaps.

For young Black students, like Natalie Douglas, who serves as president of UMSL’s Student Nursing Association, these events have helped her feel more comfortable on campus.

“This gave me a light at the end of the tunnel. Everything about this panel resonated with me. I appreciate that UMSL even hosted this kind of thing. I can say this is the first Black experience I’ve attended or even heard of,” said Douglas, adding that she is happy that the college of nursing is making steps toward progress despite pressure to regress.

Finding one’s place in their community and the movement was a recurring theme throughout the entire evening, with Call Brown emphasizing that everyone cannot do the same thing. Similarly, Dwight quotes Adrienne Maree Brown’s statement, “the small is all,” from Emergent Strategy, and encourages everyone to “find a political home and a community you can be a part of.” And with more events like this, it’s possible that home and community could be found here on the UMSL campus.